Date and Location

Accident Date:

January 30, 2021Published:

December 21, 2022Zone or Region:

Mammoth LakesLocation:

Main Bardini Chute- Sherwin RidgeAccident details

Elevation

9730 feetSlope Angle

40°Aspect

NEAvalanche Type

Soft SlabTrigger Type

Artificial - SkierSize Relative to Path

R2 - Small, relative to pathDestructive Size

D2 - Could bury, injure, or kill a personBed Surface

Within old snowAverage Crown Height

30 feetWeak Layer

Old snowAvalanche length

1800 feetAvalanche width

400 feetTerrain

Above Tree LineNumber Caught

1Avalanche Description

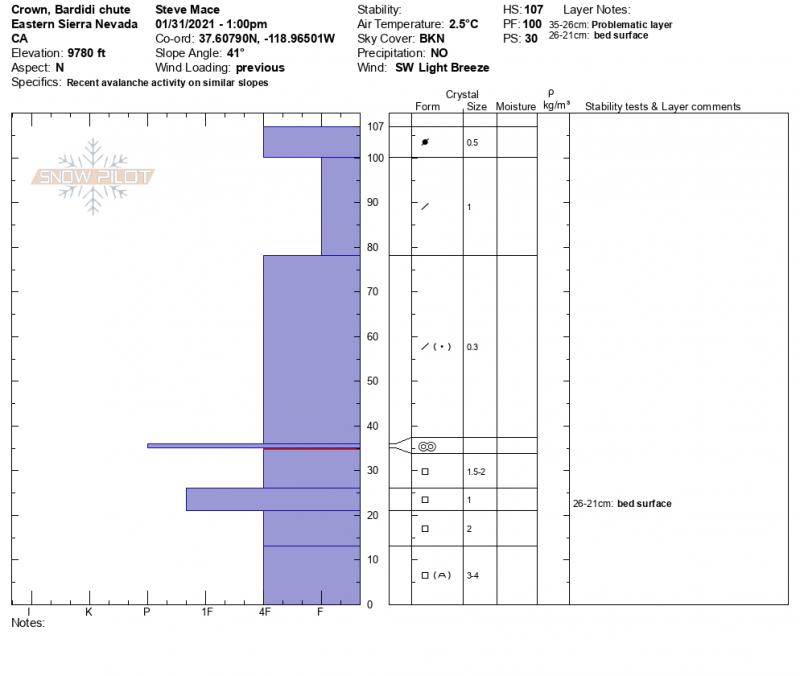

This was a soft slab avalanche triggered by the first skier to descend the slope. The avalanche was small relative to its path and had a destructive size large enough to injure, bury and kill a person. The avalanche failed on a 10 cm thick layer of large facets sandwiched between two crust layers within the old snow. (SS-ASu-R2-D2.5-O) The crown face of this avalanche averaged 70cm with a maximum height of 100cm and a width of 400 feet. This avalanche occurred in steep and complex terrain on a northwest aspect known locally as the “Main Bardini Chute” in the Sherwins. In the starting zone of this avalanche, terrain features result in frequent cross loading by the prevailing southwest flow. Some signs of recent wind transport were present near the start zone during the field investigation on 1/31/2021. The avalanche initiated at 9,730 feet and ran for about 1,800 feet in length and 1,000 vertical feet, in below treeline terrain. Skier 1 was caught, carried, and injured in this event but was not buried.

Avalanche Forecast

On the day of the incident, the Eastern Sierra Avalanche Center rated the avalanche danger as Considerable (Level 3) near and above treeline, and Moderate (Level 2) below treeline. The forecast listed Persistent Slab avalanches as the secondary problem at all elevations on northwest through north to southeast-facing slopes. The likelihood of triggering was possible, and the potential size was large to very large (up to D3). The summary statement read:

“Our recent storm provided the forecast area with a much-needed blanket of snow it has also brought about a new set of challenges. First, a significant load has been added to a minimal and, in many areas weak base. While this load may have been enough to tip the scales on its own in some areas, in others the snowpack may still be hanging in the balance. The weight of a skier might be all that is needed to trigger a large destructive avalanche. Persistent problems require persistent patience and extensive evaluation. The distribution of potential persistent slab avalanches became much harder to identify after our recent new snow. Northerly and Easterly facing terrain that still held snow from November and December are our potential problem areas. Don’t be afraid to investigate the lower reaches of the snowpack to see if old snow is present in the areas you wish to travel to. Remember that persistent slab avalanches often propagate across and beyond terrain features that would otherwise confine surface instabilities such as wind or storm slab and in some cases persistent slab avalanches can be remotely triggered from adjacent slopes. Give yourself a wide safety margin, be wary of hazards that may reside above you, and use terrain choice to limit your exposure.”

Weather Summary

The Eastern Sierra Avalanche Center measures snow and snow water equivalent (SWE) at the sesame study plot located at and maintained by Mammoth Mountain. This study plot is located about 5 miles to the northwest of this site of the incident at a similar elevation. The Mammoth area was impacted by a major winter storm in the days preceding this event. Over the course of 6 days (1/24-1/29) 102 inches of snow and 8.25 inches of SWE was recorded at the Sesame Study plot. The bulk of this (95.5” of snow and 7.93” SWE) fell over a 72 hr period from late on the night of 1/26 to mid-morning on 1/29. This snow was accompanied by strong to extreme winds out of the southwest. Temperatures remained below freezing for the entirety of this storm as well as the days preceding the avalanche.

Winds at the Sherwin ridge weather station, located about 1 mile west of the incident location at 10,100 ft, were predominantly out of the southwest for the entirety of the storm event as well as the days preceding this avalanche incident. Sustained strong winds were recorded at this site on January 29th dropping drastically in the early morning hours of January 30th. On the Day of the incident, winds were light to moderate out of the southwest with a peak gust of 25 MPH.

Snowpack Summary

21” of snow fell over the course of two storms in early November. This snowpack faceted during a 4-week period of cold, dry weather stretching to mid-December. Several small storms brought 41” of snow in the last two weeks of December and the first week of January.

3 weeks of spring-like weather led to significant settlement throughout the forecast area and the formation of surface crusts on all aspects near and below treeline. While many solar aspects were returned to bare ground many shaded aspects saw faceting and weakening throughout the entire snowpack. In the days preceding our multi-day storm event at the end of January, cold temperatures returned, and field observations indicated widespread near-surface faceting below the fore mentioned surface crusts.

Terrain characteristics in the start zone of this avalanche are such that this slope receives very little sun in the winter months. Shaded terrain like this encourages faceting and allowed for weak snow to persist through the weeks of warmer weather. Field observations from nearby terrain prior to the storm support this conclusion. In addition, this terrain is broken by large boulders, small trees, and cliff bands which further encourage faceting.

Accident Summary

A party of four toured from the Sherwin creek trailhead, known locally as the propane tanks to the top of an area in the Sherwins known locally as Punta Bardini. Along their ascent, the party observed evidence of recent avalanche activity on a feature known as the Tele bowls and decided to avoid this terrain. They also dug a snow pit to assess the recent storm snow. In this pit, they conducted multiple stability tests. A compression test broke with hard force on a density change within the storm snow. (CT 23) They did not see propagation on their ECT test. After reaching the summit the party skied one lap in the old growth and choose to transition above the Tele Bowls subsequently returning to the summit. On their second lap, they chose to descend down a low angle slope on an NNW aspect to the top of their chosen entrance to the Main Bardini chute.

Skier 1 descended a steep entrance section and triggered a large avalanche. Skier 1 was carried through complex terrain with many rocks and trees. He was able to deploy his airbag and to identify an island of trees nearby to grab onto. Skiers 2,3 and 4 immediately called 911, initiated Search and Rescue, and began their descent of the path to search for Skier 1. They located Skier 1 about 300 feet from the crown where they assessed for injuries and began a slow descent back to the trailhead.

Rescue Summary

Deep snow conditions made it very difficult for Search and Rescue to reach the site of the incident on Snow machines. Skier 1 sustained moderate injuries but was able to descend under their own power. The group of four made contact with Search and Rescue upon reaching the trailhead where skier 1 was transported to the Mammoth Lakes Hospital for further evaluation.

Forecaster Comments

All four members of this party are very experienced backcountry travelers and familiar with the terrain in which they chose to travel. They discussed the day’s forecast, conducted their own stability tests, and worked together to decide on their route choice. It should be noted that when they dug a snow pit to assess stability, they did not dig to the ground to inspect the old snow. This would have been necessary to evaluate the potential of persistent slab instabilities. While the terrain was familiar the state of the snowpack was not one typical of the Eastern Sierra Nevada.

The start zone of this avalanche averages 40° in slope angle and is littered with small trees, large rocks, and cliff bands. It is highly likely that one of these shallowly buried rocks acted as the trigger point for this avalanche. This complex terrain also increases the consequences of an avalanche in this location.

We at ESAC would like to offer our sincere gratitude to all parties involved for their candor and vulnerability. It takes courage and humility to share these details so that others can use incidents like these as learning opportunities. Thank you.

Media